Gammer Gurton's Inglecock

Another indelicate frivolity

By Mihangel

Segment 3

He was still there in the morning. I was woken, far too early, by a cock crowing. Cursing it, I found my mind impregnated with cocks: first with Gammer's allegedly stolen cock, then with Cock the boy, then with the inglecock. I became aware of William trying to tell me something. Attic, he seemed to be saying, attic. He couldn't mean . . . Or could he? Well, we must look. With that, I dropped off again.

When I resurfaced it was already after nine. I checked my mobile, finding a text from Rob that he'd be at Andover at 10.27. I swung hurriedly out of bed, washed, shaved and dressed, and went down to the kitchen. Unsurprisingly, there was no sign of the boys. But Charlotte was there, and she plied me with muesli and coffee.

On hearing Rob's message, she said, "Forget about the boys. We must leave at ten. In other words PDQ. And do you mind if we drop in at Sainsbury's on the way back?"

All I could do was scribble a note for Alex and Hugo to find when they should come down. "Look in attic for inglecock. William said so. I think."

We picked up Rob, who was an instant hit with Charlotte. We went round Sainsbury's whichtook, as usual, longer than expected, and it was midday before we were back. Rob and I, gentlemen that we were, carried the shopping in and helped Charlotte stash it away. On the kitchen table was a note from the boys that they'd fed the chickens and pigs and were now in the attic, searching. They came down, dustily, to welcome Rob with warmth and to throw me grins which confirmed that their night, as one might have guessed, had fully lived up to expectations. They returned to their search, dragging Charlotte with them, while I took Rob into the hall to introduce him to the manuscript, the new text, and the whole business of inglecocks and Jack of Hilton. As always on the ball, he readily hoisted in the complexities, and was not only fascinated but tickled pink.

"And I thought you said the Middle Ages didn't show cocks on blokes!"

"I did, except on infants and sinners in hell. Jack & Co are the exception that proves the rule. Unless they're regarded as sinners, roasting there by the fire."

Then Charlottereappeared, festooned with cobwebs, brandishing a feather duster, and excited.

"Guess what we've found!"

"Not the inglecock!"

"Better than that! We've found William!"

"Uh?"

There were footsteps on the stairs, slow and cautious, and in came Hugo and Alex, gingerly carrying something between them. It was large and flat and vertical, and its back was towards us. Grinning ecstatically, they turned so that we could see their burden.

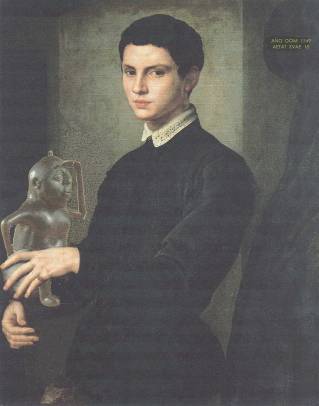

It was a portraitin a heavy gilt frame, dirty and in need of professional cleaning, but riveting. It was a young man or boy, dark-haired and attractive, very much like Alex if more shy in expression, soberly dressed in black doublet and lace collar. Behind his head, barely legible through the grime, were the words Anno Dom. 1549, aetat. suae 18. The date fitted William precisely. Most remarkable of all, perched on his right forearm and steadied by his left hand, was a Thing, podgy, bulbous and benign. It might almost have been a Thing From Outer Space, one stick-like arm akimbo, the other shading its eyes, and on top of its head was a little button.

It was a portraitin a heavy gilt frame, dirty and in need of professional cleaning, but riveting. It was a young man or boy, dark-haired and attractive, very much like Alex if more shy in expression, soberly dressed in black doublet and lace collar. Behind his head, barely legible through the grime, were the words Anno Dom. 1549, aetat. suae 18. The date fitted William precisely. Most remarkable of all, perched on his right forearm and steadied by his left hand, was a Thing, podgy, bulbous and benign. It might almost have been a Thing From Outer Space, one stick-like arm akimbo, the other shading its eyes, and on top of its head was a little button.

Charlotte gave the portrait a quick whisk-over with her duster. "Put him up!" she ordered. "There!" And she pointed to the place of honour over the fireplace. Rob and I grabbed a chair apiece and climbed up to remove the current incumbent, a bewhiskered Victorian Stevenson who looked grumpy at being displaced. We dumped him against the wall. Rob took over from Alex who was hardly tall enough to reach, and he and Hugo lifted William and looped his hanging-chain over the hook. In deep content, we stood back to gaze. He was well-lit from the windows, and the whole room seemed filled with a glow of approval. It made Rob look curiously around.

"It's William, Rob," Alex explained. "He's here. In spirit, I mean. And isn't he great! Till now, we've never known what he looked like. It is William, isn't it?"

"Oh, it must be," I said. "1549, aged 18. And that must be his inglecock that he was so fond of. Not wanking, though. Its hands are in the wrong place. And if it's got a hard-on, the painter's discreetly hidden it behind William's hand." It was incautious of me, I realised too late, to say things like that in front of Charlotte. But she was laughing with the rest.

"But why was he banished to the attic?" asked Hugo. "The most famous Stevenson of them all?"

"Do you think," I suggested, "it was in Victorian times? Someone like him" -- I pointed at the bewhiskered Victorian who was glaring at us from the floor -- "was so shocked by the inglecock that he banished it. Remember what it said in the article, how the owner of one of the inglecocks chucked it into a pond, having hacked off its cock? And do you think he banished the portrait at the same time because William was holding that disgusting inglecock? And because he'd written that shameless play?"

"Well, if he dumped William in the attic, did he dump the inglecock there too? Let's have another look!"

Off Alex and Hugo dashed, ignoring Charlotte's cries that it was time for lunch. We old ones -- it struck me with horror that I was counting Rob and myself as old ones -- shrugged at the impetuosity of youth, and went in search of food. But by common consent, having filled our plates with bread and cheese and pickles and our glasses with OJ, we took them back to the hall. There we continued our communion with William -- with the portrait, that is, for the presence had wandered off, perhaps to the attic to help the boys.

Barely had we finished than there came a yell of triumph from upstairs. Down they came and, wonder of wonders, Alex was carrying the Thing itself. No, not itself. Himself, for from this moment I regarded him as a person. He was exactly as in the portrait, except that his very substantial member was on proud display. He was placed carefully on the hearth and, like worshippers before an idol, we knelt down to inspect him. He was not only better endowed than Jack of Hilton (even if lacking those balls), but better designed and made. He was . . . well, beautiful is probably the wrong word, so let us call him lovely. The bewhiskered Victorian seemed to be gnashing his teeth, until I turned his face to the wall. And through the whole room spread a sense of quiet satisfaction.

Barely had we finished than there came a yell of triumph from upstairs. Down they came and, wonder of wonders, Alex was carrying the Thing itself. No, not itself. Himself, for from this moment I regarded him as a person. He was exactly as in the portrait, except that his very substantial member was on proud display. He was placed carefully on the hearth and, like worshippers before an idol, we knelt down to inspect him. He was not only better endowed than Jack of Hilton (even if lacking those balls), but better designed and made. He was . . . well, beautiful is probably the wrong word, so let us call him lovely. The bewhiskered Victorian seemed to be gnashing his teeth, until I turned his face to the wall. And through the whole room spread a sense of quiet satisfaction.

"He's no taller than Jack," Hugo pointed out. "But his cock's a big improvement. Just what we wanted. Look, he's got to have a name, like Jack of Hilton. What about Cock of Bumley?"

"Hey!" said Alex. "I'mCock of Bumley. You can't have two Cocks! Why not Jack of Bumley?"

As I gazed, I was inspired. "It's his cock that matters!" I cried. "Look at his cock! In those days, needlecould mean a cock. And his cock's just like a needle! Remember what William wrote? How Hodge describes Gammer's needle?

"A little thing with a hole in the end, as bright as any silver,

Small, long, sharp at the point, and straight as any pillar.

"Wasn't he thinking of thisneedle? Thiscock? It's got a hole in the end, it's long, it's sharp, and and it's straight. As they sat round the fire that evening, weren't they joking about this needle? Isn't this what gave William his big idea? 'Ha!' he said. 'Myplay's going to be about a needle!'"

"That's right!"the presence seemed to say.

"So should we call him the Needle?" I asked. "The Bumley Needle?"

Charlotte dragged the boys to the kitchen to force-feed them with some lunch, and as they went they shouted, "There's an ancient fireback up there too. And a whopping big pair of stand things. Far right-hand corner."

So Rob and I went upand found them. The fireback was decorated with a complex coat of arms, and the 'stand things' were large fire dogs to support the logs burning on the hearth. With much grunting, for they were all of solid iron, we carried them down and, having removed the basket grate, set them in place. Rob then went into professional mode. He toyed with the Needle, stroked him, tapped him, shook him, peered at him from every angle.

"Intriguing," he declared. "So simple. Apparently so effective. But how effective is he really? Shall we ask if we can try him?"

"It won't hurt him?"

"I don't see how it can. He's good thick bronze. He isn't cracked at all."

And Charlotte, when asked, agreed. So Rob laid the fire and, with the help of newspaper and a firelighter which would hardly have been available in Tudor times, got it going. Then he weighed the Needle on the kitchen scales, filled him with water through the hole in the back of his neck, and whittled a bung from a piece of kindling. With everybody crowded around, he ceremonially placed him beside the logs. The fire blazed merrily, and we waited until a good bed of ashes should accumulate and the inglecock should heat up and show his paces.

"Let's make sure I've got this right," Rob said. "When Cock's impaled by the Needle he's indoors and out of sight. When he emerges he's still impaled, until Hodge pulls the cock out. That right?"

"Yes."

"Two problems, then. First of all, we can't use the real Needle. Even when empty he weighs fifteen pounds. Much too heavy to be dragged along behind, even if Cock crawls out on hands and knees. So what we need is a light-weight mock-up. Papier-mâché, I'd suggest. And bigger, to make him more obvious to people in the back row. OK?"

We chewed it over, and it made every sense. "Can you make one?"

"Yes, I could, though it'd take a bit of time. But the other problem's tougher. Weknow what inglecocks look like, and what they're for, and how they work. But who else does? The audience'll hear Cock yelling that he's been spitted by the inglecock, but they won't have a clue what he's on about. They'll see him crawl out with a weird thing up his bum -- or supposedly up his bum, unless you're going in for ultra-realism -- but they won't have set eyes on one before. They won't have a clue what it is. The joke'll fall flat. And I'd guess the same applied originally. Like us, William and his mates knew all about it. But you say that these things weren't common. So how many of the original audience would have cottoned on?"

There spoke the voice of cold reason, and it was a dampener.

"Maybe that's why those lines were crossed out," I suggested. "OK, they may have been too coarse even for Christ's. But did William realise, even though the joke was good, that it couldn't be staged? And that anyway the joke would fall flat?"

"So does it mean," Hugo asked dejectedly, "that wecan't stage it either?"

Rob, intent on the hearth, was not listening. The rest of us sat morosely, sweltering on an August day in the heat of a big fire. Its first blaze was dying off. And at that point we became aware that the Needle was beginning to whistle, or rather to hiss. His cock indeed looked at if it was pissing into the fire, and the jet of steam from his mouth could not be seen. But when Rob gingerly redirected its aim, the effect on the glowing logs was immediate. They flared up again and Rob, risking scorched hands and face, was studying the flames close-up and testing the force of the jet by holding a short-lived piece of paper in it.

"Impressive!" he said, retreating. "And the colour of those flames . . . it's giving me ideas . . . But you were saying. No, we don't have to drop the whole thing. One way round is to use the programme notes to explain. There willbe programme notes, won't there? A learned discourse by Hugo Spencer about our revered Founder, about Gammer's place in literary history, about the new manuscript, about the production?"

Hugo blushed. "Oh yes." I knew that his discourse was already in draft. He had consulted me a number of times. After yesterday and today, it was going to need a lot of revision.

"There you are, then. Include a bit about inglecocks and how they worked."

"Lots of people, though," Hugo pointed out, "don't read the programme before the performance. They're too busy gabbing to their mates. But it's dawning on me -- there ought to be a special advance exhibition of what we've found here. Old Persimmon and the headmaster'd jump at it. Display the manuscript -- though we mustn't release the new lines in advance. And the portrait. And the Needle, with a diagram of how he works. Always assuming," he turned to Charlotte, "that you'd be willing to lend them."

"They're not mine to lend. The house and its contents are Alex's, in trust till he comes of age. Though as a trustee I may have a say. In which case I'd say yes."

"And so would I!" cried Alex, his face aglow and not only with the heat.

"Good," said Rob. "The more ways of hammering the message in, the better. The other thing I'm wondering about means redesigning the set. How about this? Gammer's house -- just Gammer's, not Chat's -- has a removable front, sliding on rails. When the audience comes in, the curtain's already up and you can see the inside of the house as well as the street. People are being ordinary. Gammer's sewing. Chat's passing by. Hodge is picking up his spade to go digging. Cock's feeding the hens and pigs or something."

"Oh, can we have real hens and pigs?" asked Alex eagerly. "Ours. Or some of them. In the street. They'd add extra colour."

My heart sank. There's an old theatrical saying that infants and animals on stage invite disaster. Mercifully, my suggestion of a dummy cat rather than a real one had already been adopted. "That's only a detail, Alex," said Hugo, very properly. "Go on, Rob."

"And Tib's tending the fire against the back wall -- the room needn't be deep. The Needle's very prominent and appears to be blowing on the logs. We can't have a genuine fire, of course -- health and safety -- but I could rig up one of those electric fires with a realistic flame effect, and use a rheostat to make it glow brighter and brighter. So there'll be plenty of time for the message to sink in, that that's what an inglecock looks like, and that's what it does. And then a drop comes down, dividing the street from the house. We won't need much time to roll the house front in, and with nylon runners it shouldn't make any noise. So at that point Diccon toddles on, says the prologue, and toddles off. The drop goes up, and off you go. What about that?"

Trust Rob to work out the practicalities. There was eager agreement. And Alex resurrected the idea of his livestock. He dragged us into the garden to admire them. I hadn't set foot there before, and it was very charming, not because it was neat and tidy, which it wasn't, but because of its setting between the mellow brick walls and the little River Didder which chuckled past. Alex clearly had a way with animals. There was a large coop for the chickens, and a large run. He clucked endearingly to them and they came running. Hugo clucked endearingly to them and they scuttled off in horror. Scope for a laugh there, I admitted, could it be repeated on stage. Then the pigs. Two large sows, one a very recent mother with a tribe of littl'uns. Alex grunted, and one littl'un scampered over to be tickled. "His name," Alex told us with great originality, "is Piglet. He'll be weaned by December. He'd go down a bomb." Hugo seemed halfway to being convinced, but I stayed aloof. If they joined the cast, I'd have nothing to do with them.

That night Rob joined me in William's four-poster, and William gave us his blessing. After all, it was perfectly possible that he'd tumbled his own mates in it.

*

The next ten days need not be chronicled in detail. They were a time of hard work for everyone. Charlotte potted. Hugo pondered the production and laboured over his learned discourse. Alex helped Rob. And Rob concentrated on the papier-mâché Needle. He scrunched up chicken wire to the right shape and size -- half as big again as the original -- as the frame on which to build up the skin, for which Alex mixed paste and tore up old newspapers in prodigious quantity.

Intwo areas Rob had to innovate. He argued that the audience would better understand the inglecock, when on display at Gammer's hearth, if steam was seen to be issuing from its mouth. In our experiment on the fire, the steam had been invisible because the temperature was too high for it to condense. But with a lower ambient temperature, the jet would be visible. So he built into his wire skeleton a tube running from the mouth to the back of the head. Into this would be plugged a rubber pipe leading behind the scenes to an electric kettle. Tests worked brilliantly.

Secondly, how was the Needle to be attached to Cock as he crawled, impaled, out of the house? Hugo vetoed Alex's noble offer to have it up his arse for real. Instead, Rob stitched a crudely rustic jerkin, very short in length in order to allow the Needle easy access; and, for Alex to wear under it, he adapted a pair of tight briefs. To their crotch, on the outside, he sewed a tube of fabric into which the Needle's cock fitted tightly enough to stay put as Cock crawled, but loosely enough for Hodge to pull it out. This being a matter of very delicate adjustment, endless fittings were required, which they did in decent privacy. But once I overheard them.

"Right," Rob ordered. "Pants off."

"Jerkin off?"

"If you must. But not with me. I only do it with Sam."

Inside the house and out of sight, Cock would have the Needle inserted. A saucepan would be dropped from a height to simulate the clatter as he fell backwards and knocked the Needle over. And he would emerge on hands and knees, the Needle riding piggyback-fashion on his rump.

"Can we have a sound effect?" asked Alex. "A plop when Hodge pulls it out?"

Hugo vetoed that too. "No," he said firmly. "They'll be laughing so hard they won't hear it."

It took a great deal of time before they were sure everything would work properly. But in the end it did, and Rob painted the Needle with bronze-coloured paint and varnished it. It looked as lovely as the original. And Alex made himself useful in other directions. He went with Charlotte into Andover and came back with a whoopee cushion for Rat's fart when halfway through the hole, and with a cute cat to represent Gib when Hodge is investigating her to see if she's swallowed Gammer's needle. It was actually a kitsch hot water bottle cover with a zip along its belly, into which Hodge could insert his hand and manipulate it like a finger puppet. On the web Alex found a highly realistic cat screech for when Gib dashes upstairs from the hearth, pursued by a cursing Hodge. He also searched for a recording of the distinctive noise -- let us not go into details -- produced by someone with the trots, for when Hodge shits in his pants. But without success. All we could do was agree that if, when back at school, we or any friend of ours got the trots ourselves, we would send for Rob who would come post-haste with his tape recorder.

As for me, I spent all the time on paper work. I went through the manuscript word by word, noting even the smallest variations from the 1575 quarto. Though they made no significant difference, we incorporated them into our script. I confirmed that the manuscript really was contemporary by discovering from the watermark that the paper was French -- no paper was made in England at the time -- and from a mill that closed in 1547. Shops could have sold off old stock for a few years, but not for many.

I drew some conclusions. Gammerwas certainly written, as I've said, before June 1549. It was probably written at Christmas 1548 or early in 1549, when William was seventeen. Within a year he had his portrait painted with the Needle. Our manuscript, though not the original draft which would surely have been riddled with insertions and crossings out, was a fair copy done very soon afterwards. And this copy was expurgated, either because it went too far or because that scene was unstageable. But the play wasn't performed until 1550, after he had graduated. Might that be because Christ's wouldn't accept plays from undergraduates? It all seemed reasonable enough. I only wished I could be sure the writing wasWilliam's.

The manuscript scoured, I turned to the other papers in the chest. They proved, almost all of them, to be a rag-bag of deeds, documents concerning lawsuits, household accounts, and wills, stretching from the 1530s to the late 1600s. They shed virtually no light on William as a person. It appeared that his parents had died of the plague in London in 1545, when William was fourteen. Their wills appointed as his guardian an ancient great-uncle who thereupon took up residence at Bumley. According to an inventory of their chattels, the hall there was adorned with 'j paire of dogges, j paire of billowes & j inglecocke, j paire of tonges, j fire shoule, j fire pyke.' It was nice to find the inglecock in company with the fire dogs, bellows, tongs, shovel and poker; but that mention remained, apart from Gammer, the only use of the word that I ever discovered. It may well have been a name peculiar to the Stevenson family.

My only really significant find was a small sheaf of musical scores, their diamond-shaped notation curious to modern eyes. Most of them were evidently instrumental, but one was vocal, a four-part setting of the drinking song with which Act II of Gammeropens:

Back and side, go bare, go bare,

Both foot and hand go cold;

But Belly, God send thee good ale enough,

Whether it be new or old.

The words were second-hand -- they were known from a good twenty years earlier -- but the music was pretty clearly original. We already knew, from the record that Christ's paid him for music, that William was a musician as well as a writer. The handwriting on the score was the same, as far as I could tell, as in the manuscript of the play. Several sheets of instrumental scores, moreover, bore the initials W.S. The case for authenticity was as tight as we could wish, and now we could perform not only his play but also, in the interludes, his compositions. Hugo was over the moon. He knew much more about music than I did, and he picked out the melodies on the Bumley piano which had probably not been tuned since the days of the bewhiskered Victorian.

"We'll sing the drinking-song off-stage," he said. "All of us. It won't be professional, but songs in pubs aren't, are they? And for the interludes we'll rope in some musicians. Recorder -- easy. Crumhorn -- I think it's blown like the bagpipes, and Tam McLoony's a piper. Sackbutt -- any trombonist. Bass viol -- surely a cellist can do that. But apart from the recorder, I doubt if Hambledon can run to any of those instruments. I'll have to twist Old Persimmon's arm to hire them."

Finally, I scanned every sheet of the manuscript and the music and put them on CD, and got Rob, who had his camera with him, to take photos of the Needle and the portrait.

*

Everything, therefore, was going very well. But there was a major worry niggling at my mind, and I knew I had to be stern about it. One evening I broached the matter to Charlotte and Alex.

"What are you planning to do with all this stuff?" I asked. "The manuscript, the music, the portrait, the Needle? Are you going to keep them? Here?"

"We haven't thought about it," Charlotte said. "Oh I see! You're wondering about insurance. That's a point. Insurance companies are ghouls and vampires, and I pay them too much already. What might these things be worth?"

I drew a deep breath. "The Needle, I haven't the foggiest, but a lot. The portrait, simply as a good Tudor portrait, I'd guess a few grand. But it's probably the earliest known portrait of an English playwright, which could well push it up to a hundred grand or more. And being the only portrait of the Founder, Hambledon would give its eye teeth for it. As for the manuscripts . . . well, millions. Even tens of millions. OK, that's all guesswork. But you're talking about megabucks, no argument."

Their eyes had been growing wider and wider.

"Your main headache's security. If this place was burgled, or burnt down . . . it doesn't bear thinking about. At the very least you'd have to get a fireproof safe and a controlled environment to keep the manuscripts in. It's lucky the roof hasn't leaked on them already. And as soon as we do Gammerin December, news will get out that they exist, and you'll have hordes of scholars beating a path to your door and demanding to see them. What they need is a happy home where they can be looked after properly and safely, and where scholars can consult them."

There was a long silence. "So . . ." said Charlotte at last, "if we sold them . . ."

"Mum!" cried Alex. "We can't do that! We've sold off enough already! We don't want megabucks! And they belong here! They're William's!"

"Agreed, we don't want megabucks. I'm not suggesting they go on the open market where they'd be snapped up by some billionaire in America. That's the last thing we want. But somemoney wouldn't go amiss . . . Sam, I think I see where you're heading. But spell it out."

"Hambledon would be a very happy home. After all, it's William's place too. Give them to Hambledon, as soon as possible. At first only on loan. If there's going to be an exhibition they'll be needed there anyway. The portrait'll go up in a place of honour. The manuscripts would go to the archive room, which can look after them professionally. Then get them valued and start negotiating a sale, at whatever price you want. If you pitch it too high -- tens of millions -- even Hambledon might balk. But if you ask a million, say, it'll probably launch an appeal to parents and Old Boys, and will probably get it. The Arts Council might well chip in. And include as a condition that the school gets copies made of the portrait and the Needle, for you to keep here. Really good copies, indistinguishable from the originals. And of course talk to your solicitor first."

"Oh God!" cried Charlotte. "It's tempting! Fancy having a million! To see Alex through school and university. To get this place in order. To have some security at last. Alex, what do you think?"

To cut a very long story short, Alex, much mollified by the thought that Hambledon was also William's place, gave his approval. More important, perhaps, William himself gave his approval. Next day Charlotte went to Winchester to confer with her solicitor, who gave his approval too. The day after that we loaded the chest, the Needle, the portrait and all five of us into the Volvo -- a good thing Volvos are spacious -- and drove in state to Hambledon to meet, by appointment, with Old Persimmon, the archivist, and the headmaster. They went into raptures, and needed no persuading to take everything into their care, at first on loan and later, should all go according to plan, as a purchase at a price to be agreed. They enthused about an introductory exhibition. Rather anxiously, being unsure if it might prove too much even for the tolerant Hambledon, we showed them the newly-found text, but they rose to the occasion.

"If that's what the Founder wrote," they said, "that's how it must be performed."

But Charlotte and Alex laid it down as a condition that no details of the new text should be released before our performance. It was, in this respect, to be a world premiere.

"Champion!" Old Persimmon declared. "I'll invite all the leading scholars and critics, and tell them to come prepared to be hit between the eyes."

We had been afraid that William might emigrate to Hambledon along with his impedimenta, but on our return we found him still at the Grange, and at the Grange he remained.

Authors deserve your feedback. It's the only payment they get. If you go to the top of the page you will find the author's name. Click that and you can email the author easily.* Please take a few moments, if you liked the story, to say so.

[For those who use webmail, or whose regular email client opens when they want to use webmail instead: Please right click the author's name. A menu will open in which you can copy the email address (it goes directly to your clipboard without having the courtesy of mentioning that to you) to paste into your webmail system (Hotmail, Gmail, Yahoo etc). Each browser is subtly different, each Webmail system is different, or we'd give fuller instructions here. We trust you to know how to use your own system. Note: If the email address pastes or arrives with %40 in the middle, replace that weird set of characters with an @ sign.]

* Some browsers may require a right click instead